Why you Hate Literature Review and 7 Ways to Fix it

I enjoy literature review more than you do.

Ok, let me rephrase that. I don’t exactly enjoy reviewing the literature. But I hate it much less than I used to.

See, the academic literature has a few defects—a few flaws that make it a challenge to read. I’ve realized that I cannot fix these defects. But I can avoid them. I’ve developed my literature review strategy to do just that. And it’s made all the difference in changing a painful, unproductive experience into something much more effective. Something that’s almost enjoyable.

I want you to experience that change, too.

But before I explain my strategy, let’s lay a little groundwork. Let’s build some solidarity and whine about what makes the literature so painful to begin with.

Pain Point #1: journal articles are hard to read. It’s one of the great ironies of science: researchers make exciting discoveries and then dull them with dense, boring writing. You’ve likely stumbled through plenty of wordy passages like this one:

“The qualitative agreement between caribou’s preference for feeding on young leaves and the trend for protein to decline with leaf age supports the hypothesis that caribou migration is driven by the patterns of leaf-out and maturation spatially and temporally through their home range, rather than by weather.” (Schimel)

Pain Point #2: journal articles are abundant. The only thing worse than bad writing is lots of bad writing. And the academic literature has plenty of it. Hordes of rubbish bury the decent articles you’d like to read. You can spend endless hours sifting through it all.

These pain points aren’t your fault. You cannot fix them.

But you can avoid them! Well, maybe not completely. But with a few adjustments to your goals, strategies, and rhythms, you can dodge the worst of it.

Below are 7 fixes to help you do just that. I can’t promise that these fixes will help you enjoy literature review. But you’ll hate it much less, at least. And you’ll find that it’s much more productive.

In this Article

too long; didn’t read?

Download my Literature Review Guide

Set realistic goals

Why do you read the literature? No, really—ask yourself why.

Is it to grow your academic knowledge? Maybe some older person in a tweed jacket encouraged you to read the literature. Maybe they suggested that reading many journal articles will magically increase your understanding. Maybe they insinuated that good researchers constantly read the literature, ever honing their wisdom.

That goal will disappoint you. It takes years to accrue the kind of knowledge that you’re chasing. You’re asking too much of the literature. And months from now—when you’ve read scores of articles and have more questions than when you started—you’ll feel frustrated. You’ll wonder why the literature is so slow to share its wisdom. You’ll feel daunted by the mountain of reading before you.

Abandon that goal. Replace it with something the literature can more easily give you: use the literature to advance your research project.

A good literature review advances your project on many fronts. It helps you design a novel research question. It sparks useful ideas for your experiment. It seeds your journal article’s first draft. These all help your project run smoothly.

But how, exactly, can you realize those benefits?

Let’s be a bit more specific with this goal by looking forward, to your project’s end—to your published journal article. If something advances your project, it will appear in your journal article’s citations. That is, by citing something, you show that it furthered your project. So if something is worth citing, then it achieves your goal: to use the literature to advance your project.

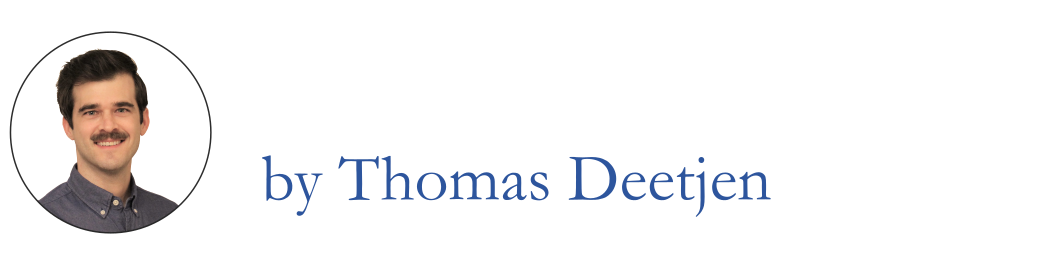

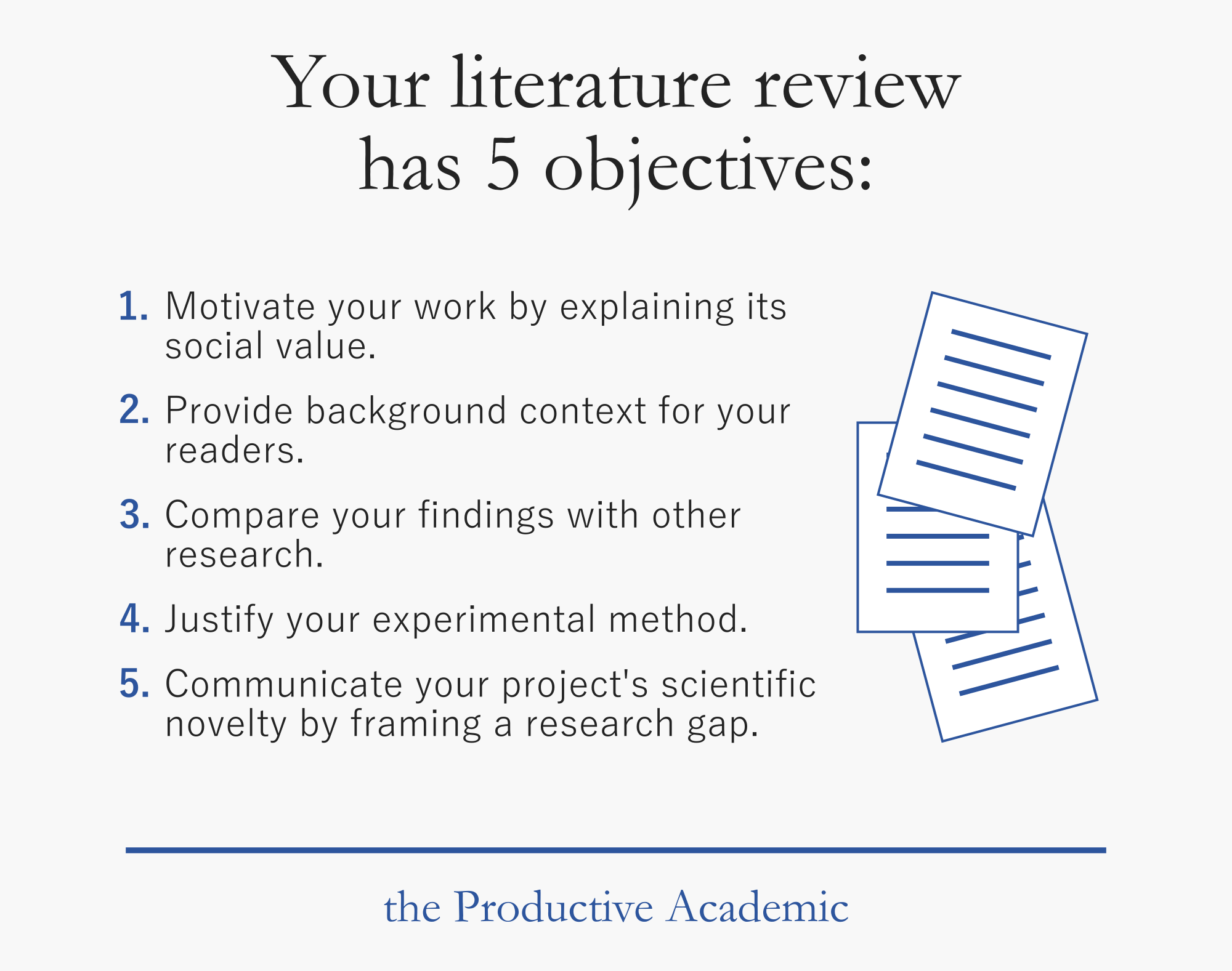

But what makes an article worth citing? Well, you can cite an article for five different reasons. I call these the five literature review objectives. If an article meets one or more of these objectives, then it’s worth citing, and it achieves your literature review goal.

These five objectives are something the literature can readily provide. If you ask the literature for knowledge, you’ll grow frustrated with how slowly it teaches you. But if you ask the literature for these five objectives, you’ll feel grateful for the literature’s usefulness.

Shift your goal toward these five objectives. It will change the way you perceive the literature. And it will change the way you review it.

2. Don’t Read. Skim

What’s the biggest mistake you make when reading the literature? You actually read it. Start-to-finish. Every poorly-written sentence.

That strategy works great for pleasure reading. But when you review the literature that way, you’ll finish each article exhausted, unsure of what you just read.

It reminds me of why I hate cycling. Now, I love a good joy ride; there’s nothing like a leisurely drive on my beach cruiser to the ice cream shop on a warm summer day. So when I joined my friend for an “easy” 10-mile tour on a borrowed road-bike, I thought I’d enjoy myself.

I was wrong. Cycling is not a leisurely joy ride. It’s fast-paced, intense, and tiring. The low-point of my first tour—exhausted, sweaty, and legs aching, I coasted to a red traffic light, braked, and slow-motion toppled into a drainage ditch. I forgot to release my shoes from the pedals.

Like cycling and biking, literature review may seem like pleasure reading on the surface. But it has different objectives. And it requires different strategies.

To review the literature, you cannot read. You must skim.

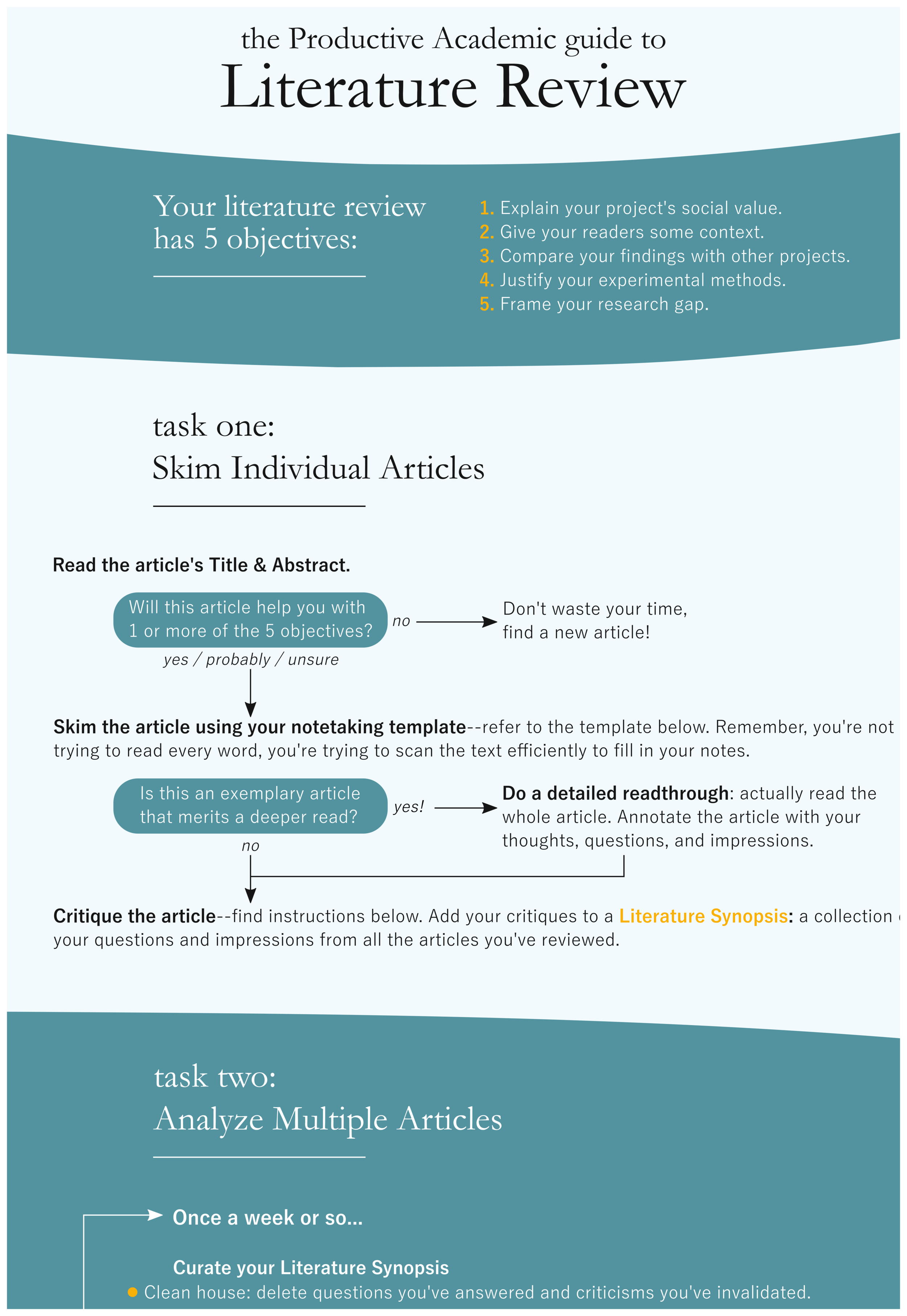

What exactly does it mean to skim? It means you review each journal article with specific goals in mind—i.e., the five literature review objectives. You hunt for the text that achieves those objectives. And you ignore everything else.

Yes, that means you will only read part of the article. You get to gloss over a lot of text. So you needn’t worry about understanding every sentence, paragraph, and figure—just the ones that meet your objectives.

Sounds dreamy, right?

To help you skim, you have two wonderful tools:

The IMRaD structure: Most scientific articles follow a similar structure: Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion—or IMRaD. Across disciplines, you can usually find the same information from the same places in the same IMRaD sections. This really helps you skim.

Your note-taking template: The template you use for note-taking gives you a checklist of things to look for when you’re skimming. It keeps your skimming on track.

What!? You don’t have a note-taking template?

Oh—I am about to blow your mind.

3. Use a note-taking template.

You are seriously underestimating the value of a note-taking template.

I know. You probably think the way you take notes now is just fine. Well, let’s put your notes to the test, then. Grab some notes from a few months ago. Using only those notes, how quickly can you answer the five literature review objectives? How easily can you compare those answers across different articles?

Not quickly. Not easily. At least, that’s what you answered if your notes are anything like mine.

My early notes wander around as they attempt to summarize each article’s every little takeaway. And each set of notes is organized a bit differently. I cannot easily compare them. I cannot use them to quickly answer the five literature review objectives. In fact, rather than navigate these old notes, it’s often easier for me to simply read the original article.

If your notes have the same shortcomings, then you’re doing it wrong. And you’re making literature review more painful.

Why do we produce such wordy, useless notes? Because we long for comprehensiveness. We yearn to read each article from start-to-finish. We worry about overlooking some useful tidbit. What if we need this insignificant little piece of information in the future? If we exclude it from our notes, how will we ever find it again?

When you put it that way, you sound like a hoarder. You’re afraid to discard any little note—however unimportant—in case you need it later. Well, you little note-hoarder, it’s time for an intervention.

You’ve traded comprehensive reading for skimming. That’s good. Now you must trade comprehensive note-taking for a different technique—one that supports your skimming.

That’s where a good note-taking template comes in.

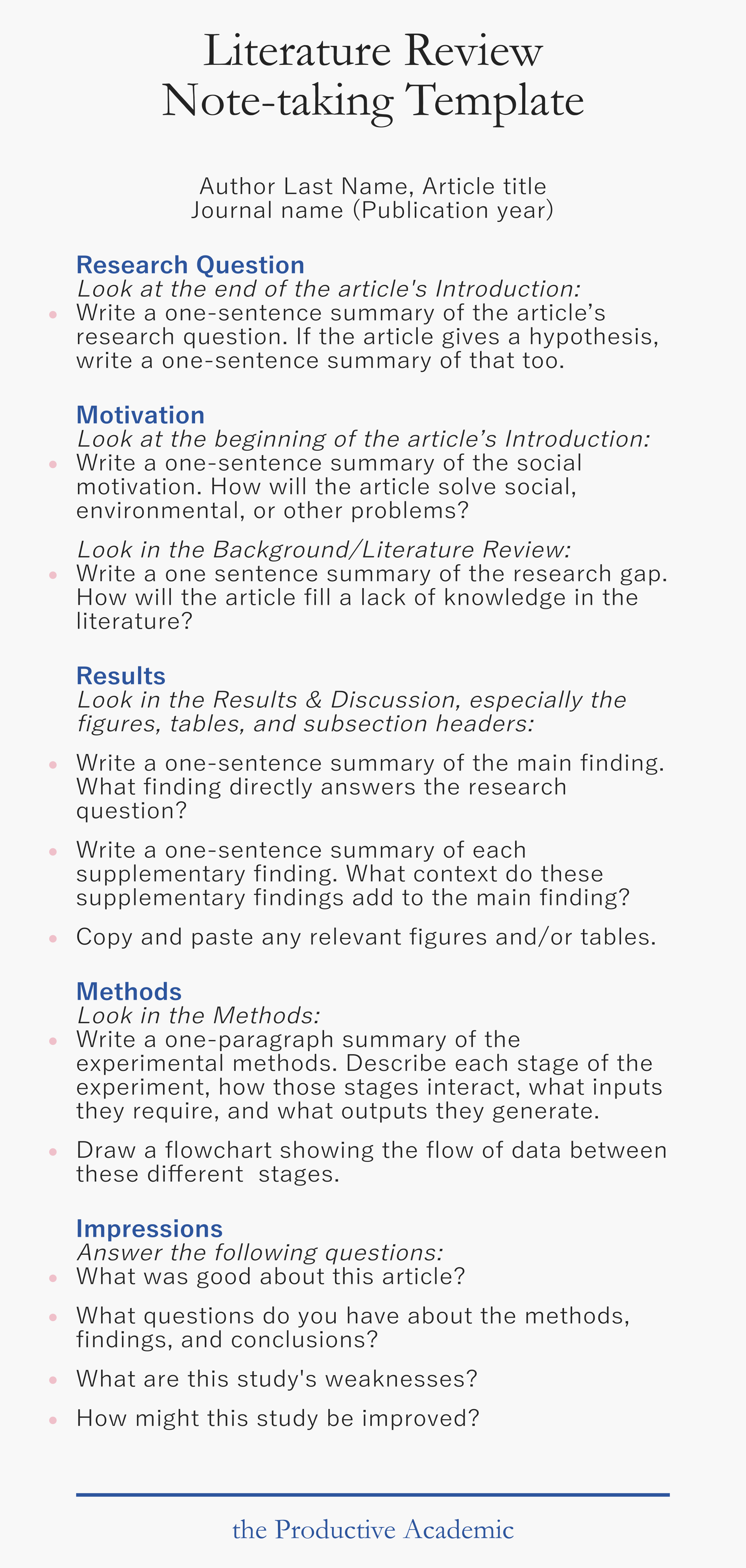

Thomas’ Note-taking Template

Here’s the template I use for taking literature review notes. It’s succinct. It’s instructive. And it aligns with the five literature review objectives. Anytime I review a new article, I start with this template and refer to it as I skim.

3 Reasons to Love Note-taking Templates

Maybe you’re still unsure about this whole note-taking template idea. Let’s convince you, then. Here are three reasons why I love using a note-taking template.

Reason 1: A template guides your skimming

One reason you undervalue note-taking templates: you think that you should read first and then take notes.

“What’s that?” you interject. “Are you saying I should somehow take notes before I read?”

Don’t be silly. I’m saying that before you read, you need to know what notes you want to take. That’s where the template comes in.

Consider grocery shopping.

Have you ever gone to the grocery store without a list? Right before dinnertime. When you’re hungry. When free samples abound. Your buying becomes…comprehensive. Every foodstuff seems like a reasonable purchase.

But when you have a list—i.e., a grocery shopping template—your trip becomes faster and more effective. Sure, the store might be out of sriracha sauce. And maybe there’s a sale on boxed wine that you must, of course, indulge. But you’ll navigate the store quickly. And you’ll leave with the items you came for.

Like a grocery list, a good template streamlines your note-taking session. It guides your hunt for useful information. It helps you know when to stop. By glancing back and forth between the article and your notes, you’ll navigate the article quickly. And you’ll leave with the items you came for.

Reason 2: A template keeps things consistent

Another reason you undervalue note-taking templates: you downplay the benefits of keeping notes that have a common structure.

When you base all of your notes from the same template, you create consistency. All of your notes are concise, are well-organized, and contain the same information in the same places.

This consistency makes it easy to find the high points of a particular article. Looking for the research question from Article X? You’ll know just where to find it in your notes.

This consistency also makes it easy to compare multiple articles. Wondering whether Articles X, Y, and Z corroborate each other’s findings? You can open each article’s notes and quickly compare their findings, which are all located in the same place of the notes’ common structure.

Reason 3: A template doesn’t hold you back

Okay, maybe you’re warming up to the idea of skimming articles and using note-taking templates. But you still see one big problem:

Some articles are actually worth reading from start-to-finish.

You’re right!

I call these “exemplary articles.” They add a lot to your project. They motivate your research, guide your methods, affirm your conclusions—and sometimes they’re even well-written! They’re diamonds among the literature rough. And a note-taking template fails to do them justice.

But a note-taking template need not limit you. You don’t have to stop once your template is full. If you find an exemplary article, by all means, explore its every detail. Here’s what I recommend:

Use the note-taking template as you would for any other article.

Mark the top of your notes with an “X” to signal an exemplary article.

Then create a second set of more detailed notes. Personally, I annotate each article directly. I’ve found that even with an excellent set of stand-alone notes, I still refer back to the exemplary article many times. So I’ve learned to just put my notes within the article; then everything’s in one place.

4. Be critical

Are you skeptical of what you read in the literature?

I wasn’t at first. When I started grad school, I viewed the literature much like a textbook. I saw it as authoritative. I envisioned world-class scientists producing high-quality research. I figured these driven, intelligent, experienced researchers must publish flawless journal articles.

That naïve position has two problems. First, every study has its shortcomings. No publication explains the whole universe. Even well-written, high-quality research has limitations. Second, science constantly marches forward. Today’s cutting edge is tomorrow’s foundational knowledge—or maybe its embarrassing blunder.

When you ignore those shortcomings, you grant the literature too much trust. You overlook each article’s limitations. And you struggle to achieve the last and most important literature review objective—finding a research gap.

Stop trusting the literature

The literature in not an authoritative textbook. Abandon this idea. Think of the literature, rather, as a collaborative book-writing project. The book’s topic is your research field. There is no editor. Anyone can contribute a chapter. And it’s far too vast to read the whole thing.

Consequently, this book veers in many different trajectories. New chapters may extend an existing direction, or blaze an entirely new path. Old chapters may give foundational knowledge or lead to dead ends. Regardless, every chapter will argue its own importance.

Reading such a disorganized book is both daunting and confusing. Which parts are worth reading? Which chapters are dead ends? Where should you add your own chapter?

It’s difficult to know—but at least you’re asking the right questions.

Your field’s literature—the haphazard, collaborative book that describes your field’s ongoing research—is full of gaps. Its journal articles promise exciting new directions. But they also suffer weaknesses, embrace underdeveloped ideas, and pursue unproven directions.

It’s your job to find those shortcomings and use them to identify a promising research gap. You’ll craft a research question to fill that gap. And you’ll design a project to answer that research question. If all goes well, you’ll contribute a new chapter that advances the cutting edge of your discipline in a worthwhile direction.

But first, you must find your research gap.

Find the research gap

Okay, that’s enough abstract discussion and metaphor. Let’s move on to something more practical. How, exactly do you find a good research gap?

Step 1: Critique Individual Articles

First, look for shortcomings in each individual article.

As you review an article, fill in the note-taking template’s first four sections, then take a few minutes to critique the study. What was good about it? What questions do you have? Where did it fall short? What would you change?

When I critique a study, I like to pretend that I’m a consultant. The author wants to improve their article. And they’ve hired me for feedback. This perspective keeps my criticism constructive. (It also mellows my tendency to ruthless judgement: I don’t want to lose my client, after all.)

I sort my feedback into four categories:

No need to answer all of those questions—they’re meant to jumpstart your critical thinking. Wrestle with the article for a few minutes. Then list your most important criticisms. And drop those criticisms at the end of the note-taking template, in the Impressions section.

Step 2: Critique Multiple Articles

You cannot find a research gap by critiquing individual articles alone. Research gaps cover broad portions of the literature. They span multiple journal articles. To find a promising research gap, you must take different articles’ shortcomings and combine them into more pervasive weaknesses.

Start by merging part of each article’s notes into a single document. I call this document the “Literature Synopsis.” It has two sections:

In the Ledger section, simply list each article’s research question and cite the article. This lets you quickly browse your literature review’s high points.

In the Impressions section, copy weaknesses, questions, and criticisms from the end of each article’s notes. By tracking every article’s shortcomings in one place, you will notice pervasive research gaps more easily.

After you review an article, simply copy these two items into the Literature Synopsis.

Then once a week or so, sit down with your Literature Synopsis. Curate it. And scrutinize your collection of the literature’s shortcomings.

Clean house: As you review the literature, your initial judgements may waver. Look through your impressions. Delete weaknesses you’ve found support for, questions you’ve answered, and criticisms you’ve invalidated.

Organize: Sort the remaining impressions into categories. Define broad weaknesses that explain the shortcomings of multiple articles. Identify sweeping questions that underpin your criticisms of multiple articles.

After a few of these curating sessions, you’ll refine your scattered critiques into a handful of succinct, piercing weaknesses. You’ll be able to define these weaknesses, describe their impact on the research field, and cite a number of articles that exhibit them.

Step 3: Combine the weaknesses

Okay, you’ve identified a few pervasive weaknesses—great! Now, let’s use them to develop a research gap for your project.

The easiest way to do this: take one of those weaknesses and make it your research gap. This gap will be simple, but defensible. The project will be modest, but useful. And that’s just fine—especially for your early research work.

But maybe you want a project that’s a bit more innovative.

If so, you can find a more novel research gap by combining multiple weaknesses. Weakness A and weakness B make fine research gaps on their own. But what happens when you consider weakness A and weakness B together? How do they accentuate each other? How do they undermine each other? What’s their overlap? What deeper research gap do they reveal together that neither of them reveal alone?

Whatever method you use, complete your research gap brainstorm session by writing a brief summary. In this summary, you’ll

Define the research gap: Identify its different features. Describe how it weakens the literature.

Give examples: Cite studies that exhibit different aspects of the research gap. Explain how the research gap weakens these studies. Describe how these studies fail to fill the research gap.

Explain the gap’s significance: Predict how filling this gap would benefit your research field. Imagine the new research directions it would unlock.

5. Pace yourself

Well, you’ve made some great headway. You adopted some new literature review objectives. You adjusted your reading and note-taking strategy to match. And you learned to use those notes to help you find a research gap.

Now you just need to apply these tools and review some actual articles.

Literature review is best done over many weeks at a slow-and-steady pace. But that sounds a bit daunting, doesn’t it? A slow-and-steady pace often clashes with our tendencies. For example, you likely lean toward one of two tendencies:

You tend to procrastinate: There are so many articles to review. Delaying it by a day or two won’t make much difference. And you have more important things to do this week. Slow-and-steady feels a bit excessive.

You tend to overachieve: You’re ready to conquer the literature review process. You want to check it off your to-do list ASAP so you can put it behind you. Slow-and-steady feels a bit sluggish.

But those tendencies only make literature review more painful.

When you procrastinate, literature review becomes a heavy, nagging weight. You know you should be doing it. But it lacks enough urgency to demand your attention. And the longer you put it off, the guiltier you feel.

When you overachieve, literature review becomes an unsustainable sprint. You start off strong. But you lose momentum after a week or two. You feel worn out. And you’ve neglected other responsibilities for too long. So you’ll give up prematurely. And your half-done literature review won’t advance your project as effectively as it should.

In either case, you could use a more balanced pace.

I recommend reviewing two articles each day. No more. No less. When you finish those two reviews, pat yourself on the back. Then move on with your day. This sets a steady but sustainable rhythm.

Sink into that daily rhythm. Let literature review become a slow burn, a steady drumbeat in the background of your daily routine. Tell your inner-procrastinator that reviewing two articles is easy. Tell your inner-overachiever that you’re making strong headway. Stay on top of your other responsibilities. And settle into a rhythm that you can sustain for several weeks.

6. Know when to stop

As you settle into a daily literature review rhythm, some weeks will pass. And you’ll accumulate a hefty pile of notes.

You’ll build more and more momentum. That momentum nurtures your confidence. Each review session feels productive. Your growing pile of notes feels reassuring.

But that momentum also rouses old anxieties. What if your efforts fall short? What if you overlook some seminal study? What if your literature review collapses under scrutiny?

To bolster your confidence and calm these anxieties, you keep on reviewing. You press on until the review feels complete.

But you cannot “complete” a literature review. That stack of notes can always grow larger. Those undiscovered exemplary articles will continue to lure you. There is always more to skim, more to note, and more to consider.

Your doggedness to discover every morsel will make the literature review process drag on much longer than needed. This only make the process more painful. You must eventually stop reviewing the literature and move on to other phases of your project.

But how do you know when to stop?

You need some stopping criteria. Once these criteria are met, it’s time to for the literature review phase to end. I suggest the following:

Review those criteria each time you curate your Literature Synopsis.

Once those criteria are met, it’s time to move on to other phases of the research process. You’re ready to 1) develop your research question, 2) design an experiment to answer that question, and 3) write an article that describes your answer to that question in the context of the literature. You might still need to review a few articles going forward. But this intensive phase—where you daily review the literature to achieve the five literature review objectives—ends now.

7. Be encouraged: it gets easier

Before we end, let’s revisit where we started and consider an encouraging irony.

In fact, I think you gain an even more valuable kind of knowledge. When you use the literature to expand your academic knowledge, you build a broad, conversational understanding. But when you use the literature to support your research project, you build a deep, practical understanding. You critique the literature, categorize it, and wrestle with it. You know more than just what it says. You know whether it says something dubious or valuable. You know its shortcomings and its promises. And that knowledge yields many benefits.

One benefit of that deep, practical knowledge: reviewing the literature becomes easier.

The chart below illustrates a survey that asked if particular IMRaD sections were “easy to read.” The chart bins the answers by the participants’ career stages. I think the results give two pieces of encouragement.

First, you’re not the only one struggling to read the literature. Most students struggle with methods, results, and figures—i.e., the bulk of any scientific journal article. And many PhDs still find these sections difficult to understand.

You’re not an imposter.

Second, all sections become easier to read with experience. As you build deep, practical knowledge, it becomes easier to read the literature. This, in turn, helps you build even more deep, practical knowledge, which again makes it easier to review the literature.

You’re getting better at this.

So be encouraged! You’ve traded your old ways for better goals, tools, and rhythms. These strategies will help you finish your literature review as painlessly as possible. And your subsequent literature reviews will only get easier.

resources I used to write this article

Published by Thomas Deetjen

Perceptions of scientific research literature and strategies for reading papers depend on academic career stage by Katharine E. Hubbard & Sonja D. Dunbar

Telling a Research Story: Writing a Literature Review by Christine Feak & John Swales

Understanding Research Methods: An Overview of the Essentials by Mildred Patten & Michelle Newhart

An Introduction to Scientific Research by E. Bright Wilson, Jr.